[ad_1]

For greater than a 12 months, Adeola Fowotade struggled to recruit folks to a scientific trial for COVID-19 therapies. A scientific virologist at College School Hospital in Ibadan, Nigeria, she joined the hassle in August 2020, which goals to check the efficacy of a mixture of available medicine. Her aim was to seek out 50 volunteers — folks recognized with COVID-19 who had reasonable to extreme signs and would possibly profit from the drug cocktail. However the recruitment effort crawled alongside, at the same time as instances of the virus surged in Nigeria in January and February. After 8 months, she had managed to enlist solely 44 folks.

“Some sufferers declined to take part within the examine when approached, whereas some who agreed discontinued halfway into the trials,” says Fowotade. As soon as case charges began to say no in March, it grew to become almost inconceivable to seek out individuals. This made the trial, referred to as NACOVID, tough to finish. “We have been unable to satisfy our deliberate pattern dimension,” she says. The trial resulted in September, in need of its recruitment aim.

Fowotade’s troubles mirror these confronted by different trials in Africa — posing a significant downside for these international locations within the continent which have been unable to safe sufficient vaccines towards COVID-19. Solely 2.7% of individuals in Nigeria, the continent’s most populous nation, have been a minimum of partially vaccinated. That’s simply barely decrease than the typical fee for low-income international locations. Estimates recommend that it might take till a minimum of September 2022 for African nations to acquire sufficient doses to totally vaccinate 70% of the continent’s inhabitants.

That leaves few choices for combating the pandemic now. Though rich nations outdoors Africa have used therapies akin to monoclonal antibodies or the antiviral drug remdesivir, these must be administered in hospitals and are costly. The drug big Merck has agreed to license its pill-based drug molnupiravir to producers that would offer broad entry to the drug, however questions stay about how pricey it is going to be if it does get approval. So the hunt is on for reasonably priced, available medicine for Africa that might cut back COVID-19 signs, decrease the burden of illness on health-care programs and cut back deaths.

How COVID spurred Africa to plot a vaccines revolution

That search has confronted quite a few hurdles. In accordance with the US-run database clinicaltrials.gov, of almost 2,000 trials at the moment exploring drug therapies for COVID-19, solely about 150 are registered in Africa, and the overwhelming majority of these are in Egypt and South Africa. The dearth of trials is problematic, says Adeniyi Olagunju, a scientific pharmacologist on the College of Liverpool, UK, and the principal investigator for NACOVID. If Africa is basically lacking from COVID-19 therapy trials, then the chance of it getting access to medicine that get accepted may be very restricted, he says. “Add that to the abysmally low entry to vaccines,” Olagunju says. “Africa wants efficient therapeutics for COVID-19 as an possibility greater than every other continent.”

Some organizations are attempting to treatment this shortfall. ANTICOV, a programme coordinated by the non-profit Medication for Uncared for Ailments initiative (DNDi), is at the moment the most important trial in Africa. It’s testing early therapy choices for COVID-19 in two trial arms. One other examine known as Repurposing Anti-Infectives for COVID-19 Remedy (ReACT) — coordinated by the non-profit basis Medicines for Malaria Enterprise — will check the protection and efficacy of repurposed medicine in South Africa. However regulatory challenges, a scarcity of infrastructure and difficulties with recruiting trial individuals all current main hurdles to such efforts.

“We’ve a damaged health-care system in sub-Saharan Africa,” says Samba Sow, the nationwide principal investigator for ANTICOV in Mali. That makes the trials arduous however all of the extra crucial, notably for figuring out medicine that may assist folks in the course of the earliest phases of illness and stop hospitalizations. For him and plenty of others engaged on the illness, it’s a race towards demise. “We are able to’t wait till sufferers turn out to be severely sick,” he says.

Trials on the up

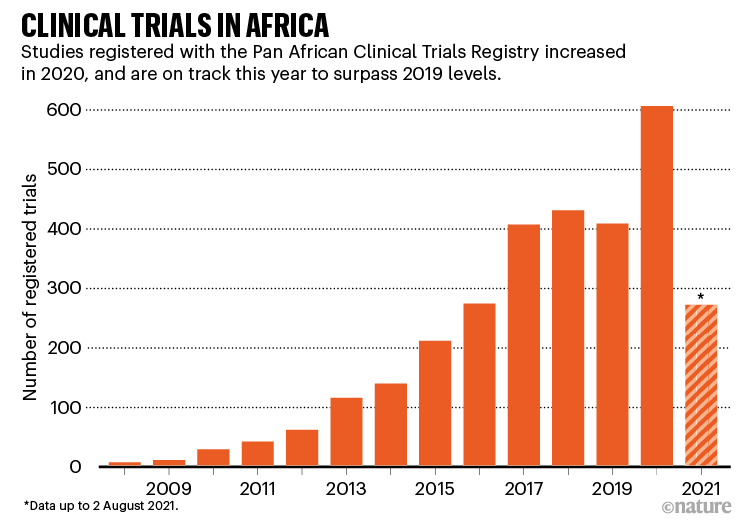

The coronavirus pandemic has given scientific analysis within the African continent a lift. Vaccinologist Duduzile Ndwandwe tracks analysis on experimental therapies at Cochrane South Africa — a part of the worldwide group that evaluations well being proof — and says that the Pan African Scientific Trials Registry registered a complete of 606 scientific trials in 2020, in contrast with 408 in 2019 (see ‘Scientific trials in Africa’). By August this 12 months, it had registered 271, together with trials for each vaccines and medicines. “We’ve seen a lot of trials increasing with COVID-19,” Ndwandwe says.

Supply: https://pactr.samrc.ac.za

Trials for coronavirus therapies are nonetheless missing, nevertheless. In March 2020, the World Well being Group (WHO) launched its flagship Solidarity trial, a worldwide examine of 4 potential COVID-19 therapies. Solely two African international locations participated within the first part of the examine. Challenges in offering health-care providers for severely sick sufferers precluded most nations from becoming a member of, says Quarraisha Abdool Karim, a scientific epidemiologist at Columbia College in New York Metropolis who is predicated in Durban, South Africa. “It was an necessary missed alternative,” she says, however it laid the groundwork for extra COVID-19 therapy trials. In August, the WHO introduced the subsequent part of the Solidarity trial, which is able to check three different medicine. 5 extra African international locations are taking part.

The NACOVID trial that Fowotade labored on aimed to check its mixture remedy on 98 folks in Ibadan and three different websites in Nigeria. Folks in that examine got the antiretrovirals atazanavir and ritonavir, and an antiparasitic drug known as nitazoxanide. Regardless that it didn’t meet its recruitment aim, Olagunju says that the groups concerned are making ready a manuscript for publication and are hopeful that the information will present some perception concerning the medicine’ effectiveness.

The battle to fabricate COVID vaccines in lower-income international locations

South Africa’s ReACT trial, sponsored by the South Korean drug firm Shin Poong Pharmaceutical in Seoul, goals to check 4 repurposed drug combos: the antimalarial therapies artesunate–amodiaquine and pyronaridine–artesunate; the influenza antiviral favipiravir, given with nitazoxanide; and sofosbuvir and daclatasvir, an antiviral mixture sometimes used to deal with hepatitis C.

Utilizing repurposed medicine is extremely engaging to many researchers, as a result of it might be essentially the most viable path to quickly discovering therapies that may be distributed simply. Africa’s lack of infrastructure for pharmaceutical analysis, improvement and manufacturing signifies that international locations can’t readily check new compounds and mass-produce medicine. Such efforts are essential, says Nadia Sam-Agudu, a specialist in paediatric infectious ailments on the College of Maryland in Baltimore, who works on the Institute of Human Virology Nigeria in Abuja. “If efficient, these therapies could forestall extreme illness and hospitalization, in addition to doubtlessly [stop] onward transmission,” she provides.

The continent’s largest trial, ANTICOV, was launched in September 2020 within the hope that early therapies might forestall COVID-19 from overwhelming the delicate health-care programs in Africa. It has at the moment enrolled greater than 500 individuals throughout 14 websites within the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burkina Faso, Guinea, Mali, Ghana, Kenya and Mozambique. It goals to ultimately recruit 3,000 individuals throughout 13 international locations.

A employee in a cemetery in Dakar, Senegal, in August as a 3rd wave of COVID-19 infections hit.Credit score: John Wessels/AFP/Getty

ANTICOV is testing the efficacy of two mixture therapies which have seen blended outcomes elsewhere. The primary blends nitazoxanide with inhaled ciclesonide, a corticosteroid used to deal with bronchial asthma. The second combines artesunate–amodiaquine with the antiparasitic drug ivermectin.

Ivermectin, which is utilized in veterinary drugs and to deal with some uncared for tropical ailments in people, has turn out to be controversial in lots of international locations. People and politicians have been demanding entry to it for the therapy of COVID-19 on the premise of anecdotal and scant scientific proof about its efficacy. A few of the knowledge supporting its use are questionable. A big examine in Egypt that supported administering ivermectin in folks with COVID-19 was withdrawn by the preprint server the place it was printed amid accusations of knowledge irregularities and plagiarism. (The authors of the examine have argued they weren’t given a chance by the publishers to defend themselves.) A current systematic evaluate by the Cochrane Infectious Illness Group discovered no proof to help ivermectin’s use for treating COVID-19 infections (M. Popp et al. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 7, CD015017; 2021).

Keep in mind Ebola: cease mass COVID deaths in Africa

Nathalie Strub-Wourgaft, who heads the DNDi’s COVID-19 actions, says there are legit causes to check the drug in Africa. She and her colleagues are hopeful that it would act as an anti-inflammatory when given alongside the antimalaria medicine. And the DNDi is poised to check different medicine if this mixture is discovered missing.

“The problem of ivermectin has been politicized,” says epidemiologist Salim Abdool Karim, director of the Centre for the AIDS Programme of Analysis in South Africa (CAPRISA), headquartered in Durban. “But when the trials in Africa may help resolve that or make an necessary contribution, then that’s a good suggestion.”

Strub-Wourgaft says that the mix of nitazoxanide and ciclesonide seems to be promising on the premise of current knowledge to this point. “We’ve encouraging preclinical and scientific knowledge that supported our choice for this mixture,” she says. After an interim evaluation final September, Strub-Wourgaft says ANTICOV is making ready to check a brand new arm, and can proceed with the 2 current therapy arms.

Obstacles and bottlenecks

Getting the trials began was a problem, even for the DNDi, which has a lot of expertise working within the continent. Regulatory approvals introduced a significant bottleneck, says Strub-Wourgaft. So, ANTICOV collaborated with the WHO’s African Vaccine Regulatory Discussion board (AVAREF) to arrange an emergency course of for joint evaluations of scientific research in 13 international locations. This might pace up regulatory and moral approvals. “It permits us to convey international locations, regulators and ethics-review-committee members collectively,” says Strub-Wourgaft.

Nick White, a specialist in tropical drugs who chairs the COVID-19 Scientific Analysis Coalition, a global collaboration to seek out options to COVID-19 in low-income international locations, says that though the WHO initiative is nice, it nonetheless takes longer to acquire approvals for research in low- and middle-income nations than it does in rich ones. The explanations embody strict regulatory regimes in these nations, and authorities which are unskilled at navigating moral and regulatory evaluate. That is one thing that has to alter, says White. “If international locations need to discover the options to COVID-19, they need to assist their researchers to do the mandatory analysis, not impede them.”

However the challenges don’t cease there. Fowotade says that logistics and insufficient electrical provides can stall progress as soon as a trial begins. She was storing COVID-19 samples in a −20 °C freezer on the hospital in Ibadan when it skilled energy outages. She additionally wanted to move the samples to a centre in Ede for evaluation, a two-hour drive away. “I generally really feel anxious concerning the integrity of the saved samples,” Fowotade says.

How COVID is derailing the battle towards HIV, TB and malaria

Olagunju provides that recruiting trial individuals grew to become much more tough when some states stopped funding COVID-19 isolation centres of their hospitals. With out these assets, solely sufferers who might afford to pay have been admitted. “We deliberate and began our trial based mostly on the information that the federal government was liable for funding isolation and therapy centres. No person anticipated that to be interrupted,” says Olagunju.

And though it’s usually effectively resourced, Nigeria is notably not a participant in ANTICOV. “All people avoids Nigeria to do scientific trials as a result of we’re not organized,” says Oyewale Tomori, a virologist and chair of Nigeria’s Ministerial Knowledgeable Advisory Committee on COVID-19, which works to establish efficient methods and greatest practices for responding to COVID-19.

Babatunde Salako, director-general of the Nigerian Institute of Medical Analysis in Lagos, disagrees with that view. Salako says that Nigeria has the information to conduct scientific trials in addition to hospitals for recruitment and a vibrant ethics-review committee, which coordinates approvals for scientific trials in Nigeria. “By way of infrastructure, sure, it could be weak; it may nonetheless help scientific trials,” he says.

Ndwandwe needs to encourage extra African researchers to hitch scientific trials in order that its residents can have equitable entry to promising therapies. Native trials may help researchers to establish pragmatic therapies. They usually can handle the particular wants of low-resource settings and contribute to raised well being outcomes, says Hellen Mnjalla, a clinical-trials supervisor on the Kenya Medical Analysis Institute–Wellcome Belief Analysis Programme in Kilifi.

“COVID-19 is a brand new infectious illness, so we have to do scientific trials to grasp how these interventions are going to work on African populations,” provides Ndwandwe.

Salim Abdool Karim hopes that the disaster will spur African scientists to construct on among the analysis infrastructure that had been set as much as battle the HIV/AIDS epidemic. “The infrastructure is effectively developed in some international locations like Kenya, Uganda and South Africa. However it’s much less developed in others,” he says.

To bolster scientific trials for COVID-19 therapies in Africa, Salim Abdool Karim suggests establishing a physique such because the Consortium for COVID-19 Vaccine Scientific Trials (CONCVACT; created in July 2020 by the Africa Centres for Illness Management and Prevention) to coordinate therapy trials on the continent. The African Union — the continental physique representing the 55 African member states — is effectively positioned to take that duty. “They’re already doing it for vaccines, in order that might be prolonged for therapies too,” says Salim Abdool Karim.

The COVID-19 pandemic, says Sow, could be overcome solely by way of worldwide collaboration and equitable partnerships. “Within the world battle towards infectious ailments, a rustic can by no means go alone — not even a continent can,” he says.

[ad_2]

Supply hyperlink